400 years ago, armies of the Czech estates and the emperor Ferdinand II encountered in the Battle of the White Mountain. It was the first battle of the Thirty Years’ War, which changed the entire fate of Europe as well as the history of the Kingdom of Bohemia.

In the Bohemian Lands at the beginning of the 17th century, the Protestant religion predominated. This, most probably, was the biggest problem and the bone of contention leading to an uprising against the monarch. The Habsburgs, on the base of the Peace of Augsburg, brought into the country the Jesuits, who in addition to the effort to bring the people back to the Catholic Church also brought higher education.

These, however, became a thorn in the Non-Catholics’ eye and there was more and more hatred towards them, which was nourished mainly with their pastoral success and also with their exceptional position. Nevertheless, the Protestants promised to be given religious freedom, first by Maximilian II in the form of so-called Confessio Bohemica (only orally not in a written form) and then by Rudolf II in the form of so-called Rudolf’s Imperial Charter (Czech: Rudolfův Majestát), which only sharpened the situation and thanks to which Rudolf was forced to abdicate.

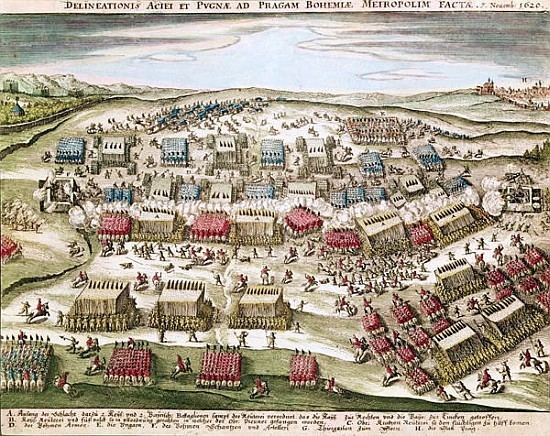

On November 8, 1620, the Imperial army moved towards Prague. The army, headed by Field Marshall Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly, consisted of well-seasoned fighting men, and their leader was equally experienced. Though the Czechs outnumbered the opposition, they were no match for the superior knowledge of the Imperial army.

The actual battle only lasted about an hour, with many of the Czechs retreating without fighting at all; Catholic losses were about 800, while the Czechs lost at least 4,000 men.

With the Bohemian army destroyed, Tilly entered Prague and the revolt collapsed. King Frederick fled the country with his wife Elizabeth (hence his nickname the Winter King). Forty-seven leaders of the insurrection were put on trial, and twenty-seven of them were executed in Prague’s Old Town Square.

Amongst those executed were Kryštof Harant and Jan Jesenius. Today, 27 crosses have been laid into the cobblestones as a tribute to those victims. An estimated five-sixths of the Bohemian nobility went into exile soon after the Battle of White Mountain, and their properties were confiscated.

The defeat of the Czech estates meant the end of the rebellion against the ruler and it entered the memory of the Czech nation as one of the most tragic moments of Czech history and as the beginning of the “Dark Age”.

-

NEWSLETTER

Subscribe for our daily news