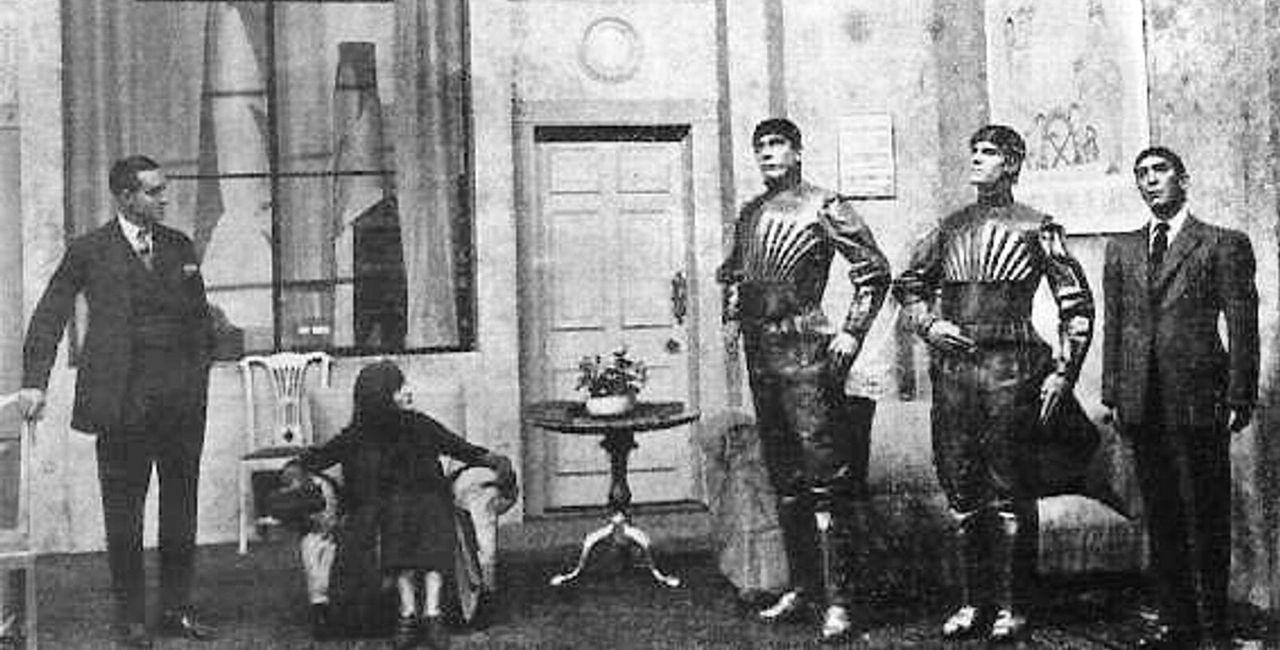

By the time his play “R.U.R.” (which stands for “Rossum’s Universal Robots”) premiered in Prague in 1921, Karel Čapek was a well-known Czech intellectual…

Like many of his peers, he was appalled by the carnage wrought by the mechanical and chemical weapons that marked World War I as a departure from previous combat.

He was also deeply skeptical of the utopian notions of science and technology. “The product of the human brain has escaped the control of human hands,” Čapek told the London Saturday Review following the play’s premiere. “This is the comedy of science.”

In that same interview, Čapek reflected on the origin of one of the play’s characters:

“The old inventor, Mr. Rossum (whose name translated into English signifies “Mr. Intellectual” or “Mr. Brain”), is a typical representative of the scientific materialism of the last [nineteenth] century. His desire to create an artificial man — in the chemical and biological, not mechanical sense — is inspired by a foolish and obstinate wish to prove God to be unnecessary and absurd. Young Rossum is the modern scientist, untroubled by metaphysical ideas; scientific experiment is to him the road to industrial production. He is not concerned to prove, but to manufacture.”

Thus, “R.U.R.,” which gave birth to the robot, was a critique of mechanization and the ways it can dehumanize people. The word itself derives from the Czech word “robota,” or forced labor, as done by serfs.

Its Slavic linguistic root, “rab,” means “slave.” The original word for robots more accurately defines androids, then, in that they were neither metallic nor mechanical.

Humans were doomed in the play even before Radius led the revolt. When mechanization overtakes basic human traits, people lose the ability to reproduce. As robots increase in capability, vitality, and self-awareness, humans become more like their machines — humans and robots, in Čapek’s critique, are essentially one and the same.

The measure of worth, industrial productivity, is won by the robots that can do the work of “two and a half men.” Such a contest implicitly critiques the efficiency movement that emerged just before World War I, which ignored many essential human traits.

Few people today know “R.U.R.” But in its time, the play was a sensation, with translations into more than 30 languages immediately after publication.

Nearly 100 years on, apart from our obvious reliance on the play’s terminology and worldview, we still hear its echoes.

The author and play title turn up as Easter eggs in such popular venues as Batman cartoons, Star Trek, Dr. Who, and Futurama: the people who portray our culture’s robots certainly know of their debt to Čapek, even if most of us do not.

-

NEWSLETTER

Subscribe for our daily news