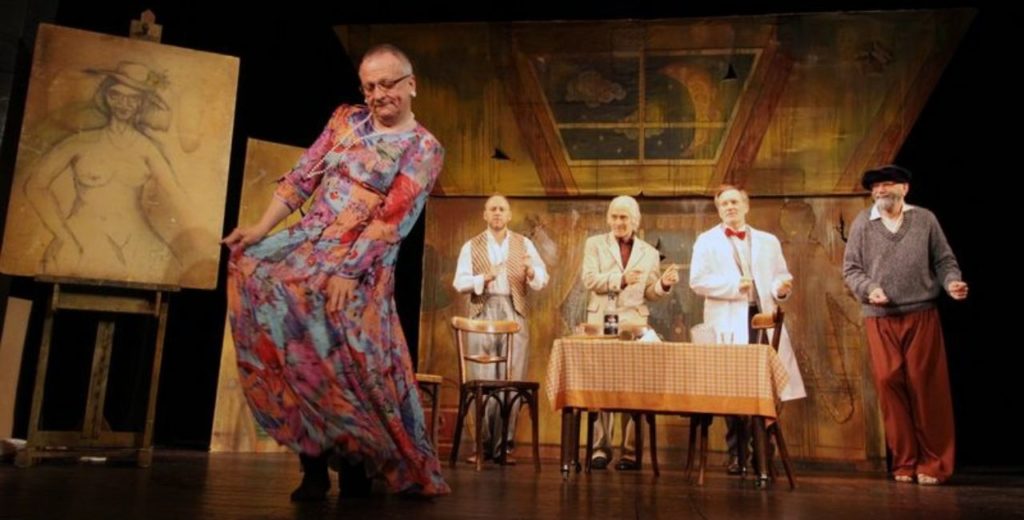

“Comedy is universal,” asserts Brian Stewart, dressed down after two hours of portraying an exasperated academic and the ditsy wife and muse of a painter.

Something of a polymath, with a lengthy career on and off the stage, Stewart, along with an enthusiastic and remarkably international ensemble cast, has spent the last 8 years committed to one project only: the Cimrman English Theatre.

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of Jára Cimrman in Czech culture. Voted the greatest Czech of all time—despite being fictional—he represents something essential about what it means to be Czech. He’s a hero who, in Stewart’s words, “never quite made it.” He is said to be responsible, though uncredited, for several scientific achievements: yogurt, the Panama Canal, and the telephone, among others.

Cimrman “captures the idea that Czechs have nobody of great prominence,” says Stewart. No other national hero has combined such determined nationalism with playful self-deprecation.

As the poet Alexei Tsetkov noted upon his departure from Prague, “I have never heard of a nation mocking itself in such a charming way.” That’s not all, though: Cimrman was an important symbol of resistance under communism and provided a platform for Czechs to criticize the regime while avoiding consequences.

Through introducing him to an English-speaking audience, Stewart has managed to translate something thought untranslatable. The project has

come under skepticism from natives, who worried that bringing Cimrman out of its original Czech would fundamentally alter the meaning and cultural importance.

“[Czechs] are very protective [of Cimrman], like an in-joke”—and rightfully so, given the way that much of historic Czech culture has been appropriated by other European nations. But according to Stewart, almost every skeptic begrudgingly agrees that the translations work—and are deeply worthwhile—after they see Stewart and his merry troupe embody the characters in a way that, Stewart feels, remains true to the source material.

It wasn’t an easy task, though. Despite the universality of most of the jokes—proven every time English audiences “laugh in the right place”—some simply would not work. Wordplay, the scourge of translators everywhere, presents a constant challenge. As a celebration of the Czech language, though—and of the Czech sense of humor—it renders itself remarkably well into English. Most of the jokes—and more importantly, the character himself—are remarkably accessible.

This is underscored by the Theatre’s success: the shows are consistently sold out, especially in the summer months when Stewart takes the play into the airy courtyard of the historic Jára Cimrman Theatre. It’s been the home of Cimrman plays for the past 55 years following multiple Communist crackdowns.

The plays are remarkable in the breadth of their satire. Beginning with a farcical conference on some aspect of Cimrman’s life that pokes fun at academics, they then launch into a more slapstick—though often profound—theatrical comedy. This month’s performance of “The Act” was no different. The full range of the witty and occasionally dark Czech theatrical spirit was on display throughout the performance.

Stewart’s project, originally conceived to enrich Prague’s English-language cultural life, has been an unimpeachable success. The Theatre began from a genuine love of the literature accompanied with the good luck of being surrounded by adept translators who felt similarly about Cimrman: most influential among them being Emília Machalová. Her lasting vision has come to define the project even after her recent departure, and Stewart is quick to humbly offload commendations her way. Hanka Jelinková, the daughter of one of the original Czech playwrights and an author herself is also vital in the making of the English translations.

Stewart’s purpose has become more defined as he has been able to observe the public’s reactions to the plays. As much as he’d like to encourage expatriates to engage with Czech culture, he’s found its role to be more personal. Czechs are bringing their non-Czech partners to bridge some cultural divide that can exist even in the most functional marriages. Moreover, young Czechs—some of whom live abroad—are returning and connecting to their roots in a way that, given the language gap, would not otherwise be possible.

This, to Stewart, is much more gratifying than appealing to a lowest-common denominator tourist audience, though some (admirably culturally-engaged) tourists do round out the audiences most nights.

But by translating Cimrman—regardless of who shows up—Stewart and his colleagues are opening Czech culture to the world. This small part of the curtain of impenetrability has been lifted, and Prague is all the better for it. Tsetkov, meditating on his inability to fully grasp Czech culture during his years writing poetry in Prague, would’ve agreed: “Jára Cimrman is consequently a secret I share with the Czechs, something an outsider will never have access to. He will remain with me as proof that I was actually more than a tourist here, though never a proper settler.”

Tickets are on sale now for The Stand-In on August 29, one of the most popular Cimrman plays. On October 21, the Theatre will be premiering a new translation of PLUM. Both will be well worth attending.

-

NEWSLETTER

Subscribe for our daily news