Charter 77, the most famous manifesto criticizing the Communist government for failing to implement human rights, came to light on January the 6th, 1977.

Charter 77 was inspired in part by the 1975 Helsinki Accords, an international treaty signed by the United States, Canada and most European countries.

The Helsinki Accords committed governments to guaranteeing basic human rights, such as freedom of speech, conscience, and assembly. But in Czechoslovakia and other communist states, these rights were routinely denied.

On 11 December of that year, several friends gathered at the home of Prague photographer Jaroslav Kořán and decided to take advantage of the Helsinki Accords.

An open letter was written, a cross between a petition and a political manifesto. There was talk of “a free, open and informal association”, made up of people “united by the desire to individually and collectively pursue the respect for human and civil rights”.

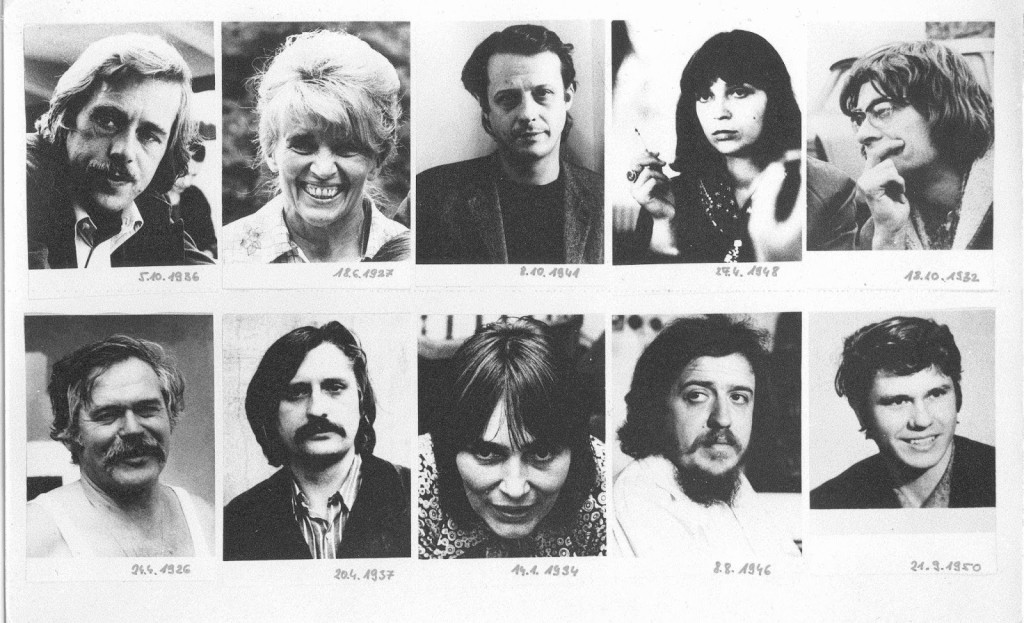

Four major editors: Václav Havel, a playwright, philosopher Jan Patočka, writer Pavel Kohout, and Jiří Hájek, the former foreign minister at the time of the Prague Spring (to whom we probably owe, the right of international law on the enforcement of agreements).

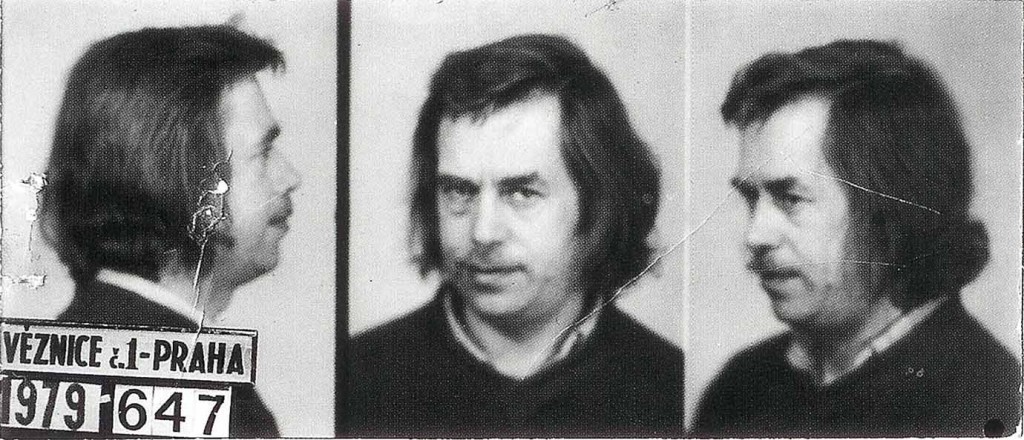

Václav Havel 1979

However, a document with a few signatures would not be worth much. The Czechoslovak Socialist Republic’s signing in Helsinki had to find a derisive echo in the signatures of its citizens. The group of dissidents began informing people about it by word of mouth, during Christmas of 1976, to collect as many signatures they could, in an activity not lacking in risks.

The identity of the first signatories was a colourful mix: academics, catholics, rockers. Signatures of those actors of the counterculture, who in their own way, lived in the “parallel polis”, as it was called by Ivan Jirous, the poet and artistic director of the Plastic People.

The largest group, which may arouse surprise, was made up of Communists Zdeněk Mlynář alone, also once alongside Alexander Dubček, gathered over a hundred signatures from old comrades of the betrayed revolution.

On January 6, 1977, they reached 241 signatures. Havel, writer Ludvík Vaculík and actor Pavel Landovský were arrested as they tried to bring the document directly to the Federal Assembly.

The letter was confiscated, but hundreds of copies were ready to circulate and reach the Western media. The next day it was published by The New York Times.

The consequences

Several signatories were arrested, and their homes searched. Havel began to get to know the Czechoslovak prisons, from which he went in and out frequently until the fall of the regime.

There are those who suffered worse consequences. On 3 March 1977, the 69 year-old Jan Patočka, among the major European philosophers, and student of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger, was brutally interrogated for over ten hours by the Prague police. Exhausted and sick, he fell ill. He died ten days later.

Demonstrations against the Chartists were organized, first forcing ordinary citizens to the streets, then exploiting the images of the most popular artists, such as singer Karel Gott and comedy actor Jan Werich.

Paradoxically, the effort to annihilate the movement (which actually just passed the two thousand signature mark in early 1990), only managed to strengthen its image. Especially abroad, where Charter 77, despite the lack of popular support, became the symbol representing communist dissidents.

Twelve years later, in the amazing domino effect of the fall of communist regimes, the small group of intellectuals, who some scholars of the time defined in the same way as a “revolutionary aristocracy”, found themselves holding the keys of democracy.

-

NEWSLETTER

Subscribe for our daily news