Tempers ran hot in Bohemia on May 23, 1618. Then, the Defenestration of Prague saw three Catholic officials defenestrated, or tossed from a window, by local Protestants.

Thanks to the grace of God or a pile of manure — depending on who you asked — the officials survived.

But the aftermath was catastrophic. The Defenestration of Prague was more than a spat between two religious sects. It encapsulated long-held and mounting tensions between Catholics and Protestants in Europe.

What’s more, its bloody aftermath would lead to the Thirty Years’ War, in which more than eight million people lost their lives to violence and famine.

So what exactly led to the Defenestration of Prague in 1618?

Long-Simmering Tension Between Catholics And Protestants

The years leading up to the Defenestration of Prague were largely defined by tensions between Catholics and Protestants. The two sects had warred for much of the 16th-century, as Protestantism spread across the continent and fractured the religious unity of the Holy Roman Empire.

In 1555, the Treaty of Augsburg established an uneasy peace between the two groups. It lay down the principle of cuius regio, eius religion, meaning a ruler could decide the religion for his land.

And though rulers of Bohemia — largely located in the present-day Czech Republic — were Catholics, they generally allowed Protestants to worship freely. Rudolf II, the Holy Roman Empire and King of Bohemia, even permitted freedom of worship in his 1609 Letter of Majesty.

But that’s where things get complicated. Though Rudolf’s brother, Mattias, kept the Letter of Majesty in place when he took power, he also named his staunch Catholic nephew, Ferdinand II, as King of Bohemia and his heir.

As the king, Ferdinand deeply desired to restore Catholicism as Europe’s only religion. He snubbed the Letter of Majesty and denied Protestants permission to build churches in the towns of Broumov and Hrob.

Local Protestants were furious. They gathered in Prague in May 1618, to see what the imperial advisors, or burgraves, had to say — and this led to the Defenestration of Prague.

How The Defenestration Of Prague Unfolded

On May 23, 1618, four Catholic deputies found themselves facing down an angry crowd of Protestants in the Bohemian Chancellery. The Protestants, led by Count Jindřich Thurn, demanded to know if the burgraves had advised Ferdinand to ignore the Letter of Majesty.

Though two of the burgraves pleaded their innocence and were released, the other two were not so lucky. Count Villem Slavata, Count Jaroslav Martinitz, and their secretary Philip Fabricius, were detained by the increasingly irate crowd of Protestants.

“You are enemies of us and of our religion,” Thurn declared. You “have desired to deprive us of our Letter of Majesty, [you] have horribly plagued your Protestant subjects… and have tried to force them to adopt your religion against their wills …”

To the crowd, he added, Were “we to keep these men alive then we would lose the Letter of Majesty and our religion, and all of us would then be stripped and deprived of our lives, honor, and property, for there can be no justice to be gained from or by them …”

Still, Martinitz and Slavata assumed that Thurn would do no worse than merely arrest them. They turned confidently toward the crowd.

“Since this concerns the will of God, the Catholic religion, and the will of the emperor,” Martinitz said, “we shall suffer everything gladly and patiently.”

But then the three Catholics were seized by the angry Protestants. As Martinitz, Slavata, and Fabricius screamed for help from the Virgin Mary, the Protestants forced them toward an open window.

Martinitz went flying out head first. Slavata clung to the window frame until someone hit him. And Fabricius was unceremoniously tossed out after them. All three men plummeted almost 70 feet to the ground below in a cacophony of “Jesus!” “Mary” and “God have mercy!”

But as the Protestants gathered at the window to peer down at their victims, they saw to their surprise that all three Catholic officials had survived.

Martinitz and Fabricius sprang up and ran away. Slavata, knocked out cold, was picked up by his servants and whisked to safety.

How did the men survive this first Defenestration of Prague? Catholics quickly claimed that divine intervention had saved the burgraves’ life. They insisted that the Virgin Mary must have heard the pleas of the doomed men and saved them.

But the Protestants said that the explanation had nothing to do with God. Instead, they declared that the three Catholic officials had merely fallen into a large pile of horse manure. The manure, apparently, had cushioned their fall and spared their lives.

Though no one died during the Defenestration of Prague, it did have a violent impact. The Catholic officials went immediately to Ferdinand to tell him what happened. And Ferdinand vowed to take revenge.

The Legacy Of The Defenestration Of Prague

The Defenestration of Prague acted like a spark in a dry field. Following the incident, a great chasm opened in Europe between Catholic and Protestant states. Bohemia soon erupted into open revolt, deposing Ferdinand II as king and crowning Frederick V, the Calvinist son-in-law of England’s James I.

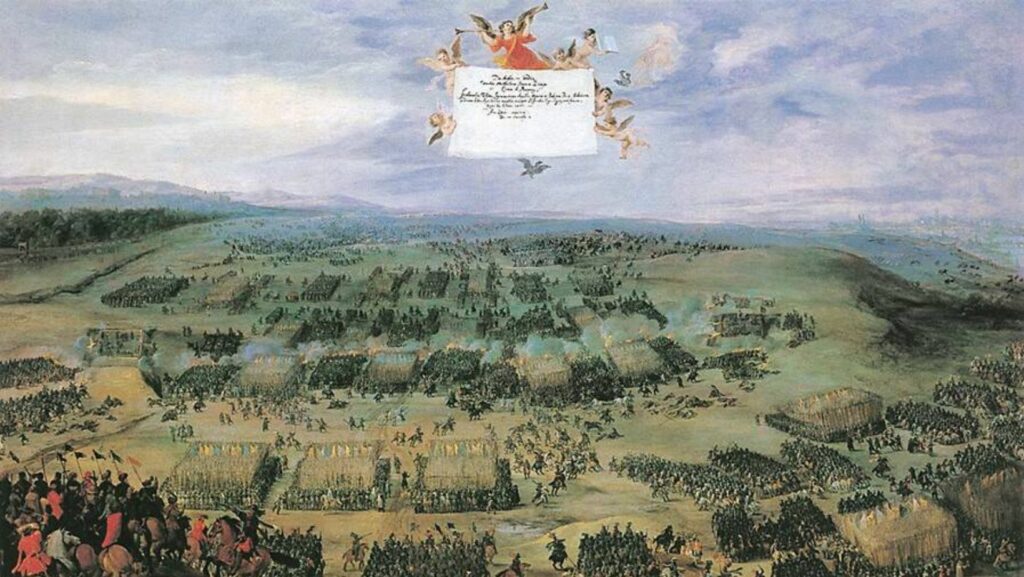

Crisscrossing alliances, religious fervor, and century-old tensions tore through the land. The Thirty Years’ War would destroy cities, obliterate farmlands, and take more than 8 million lives.

Though the conflict staggered to an end in 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia, decades of war completely transformed Europe. Spain lost power. France gained power. And Bohemia didn’t escape unscathed.

Not only did Bohemia lose its status as a kingdom, but it also failed to maintain the religious independence that Protestants defended in the Defenestration of Prague.

Protestantism was stamped out and most people became Catholics. Even the Czech language was suppressed in favor of Geman.

The window-tossing incident in Bohemia left a mark in other ways as well. Technically, the Defenestration of Prague in 1618 was the “second” defenestration in the city’s history. (The first was in 1419). And one other may have followed in March 1948.

Then, a Czech diplomat named Jan Masaryk was found dead beneath his bathroom window at the Foreign Ministry in Prague. In a spurt of Cold War intrigue, some have claimed that he was tossed to his death — defenestrated — by Communist agents.

However, others state that Masarysk died by suicide.

In the end, the Defenestration of Prague marks a single moment that changed Europe forever. It was more than just angry Protestants facing off with Catholic officials — the defenestration both embodied European unease about new religions and heralded the violence to come.

And, if nothing else, the Defenestration of Prague has also kept the word “defenestrate” firmly in the world’s collective memory.

-

NEWSLETTER

Subscribe for our daily news