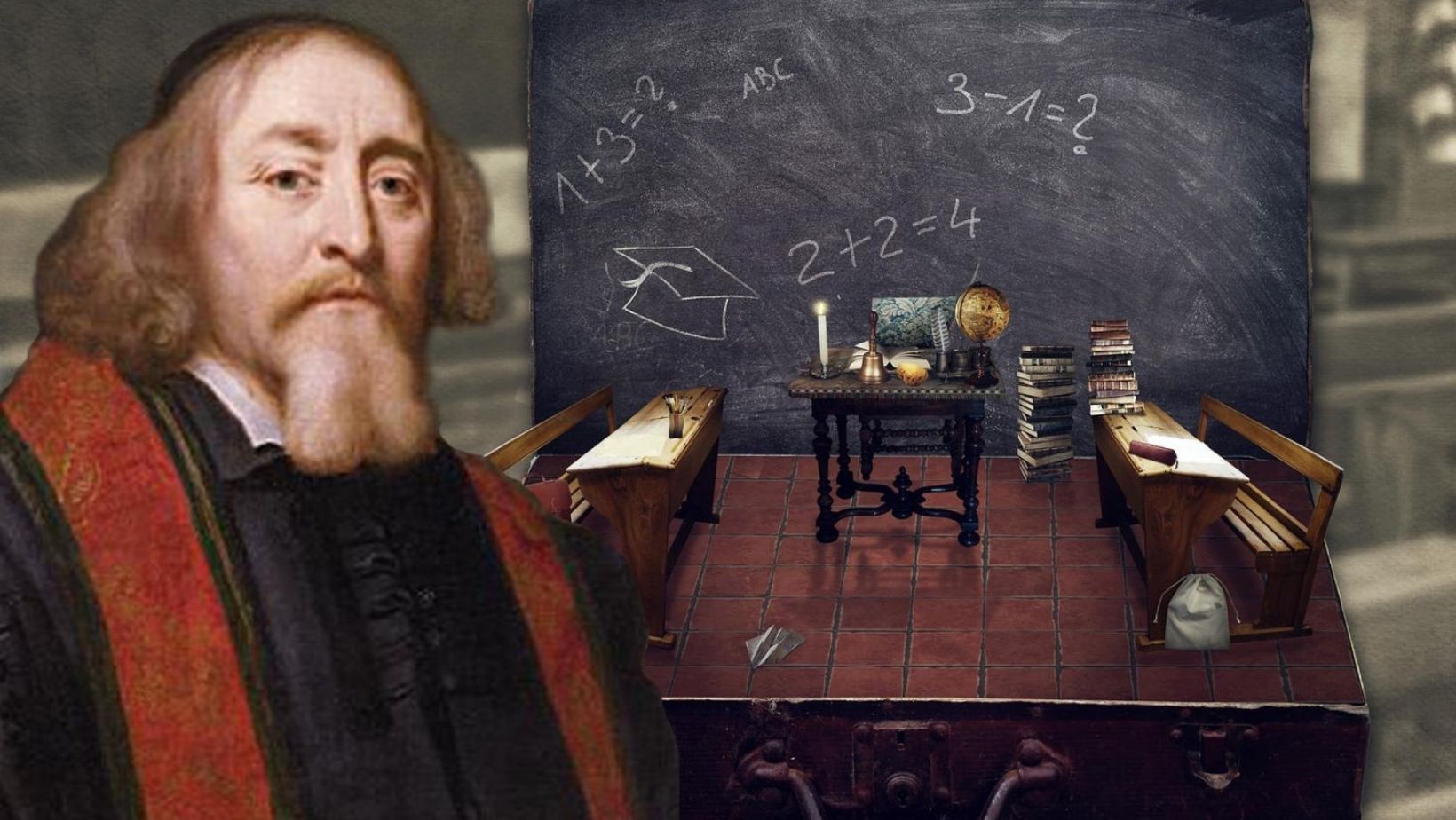

Today is the 429. anniversary of the birth of Jan Ámos Komenský, Moravian/Czech pedagogue, philosopher, and theologian, who is considered the father of modern education.

Komenský introduced a number of educational concepts and innovations including pictorial textbooks written in native languages instead of Latin, teaching based on gradual development from simple to more comprehensive concepts, lifelong learning with a focus on logical thinking over dull memorization, equal opportunity for impoverished children, education for women, and universal a practical instruction.

The Czech Republic celebrates 28 March, the birthday of Komensky, as Teacher’s Day.

His Life

Jan Amos Komenský came from southeastern Moravia, from a family belonging to the Unity of Brethren. Born on March 28, 1592, the question of his birth is controversial: Nivnice or Uherský Brod are mentioned.

The Comenius family had four older daughters in addition to their only son John. Comenius probably spent his childhood in both places in southeastern Moravia, and in 1598 he began attending a Unity of Brethren school in Uherský Brod.

The future fate of Jan Amos was decided not only by his talent, but also by the need of the Unity to have educated young ministers. Therefore, he was sent abroad to study at Calvinist-oriented universities in Germany, where he spent three years (1611-14).

He continued his studies at the University of Heidelberg. After returning to Moravia in 1614, Comenius began teaching at the Přerov school and in 1616 he was ordained as a minister.

Like most of the Unity of Brethren, he supported the Czech uprising against the Catholic Habsburgs. The defeat of the Czech and Moravian protestant states in the Battle of the White Mountain on November 8, 1620, thus marked his fate.

At the turn of 1621/22, he was forced to leave his then place of work for fear of his freedom and life and then hide in various places in northern Moravia. The new constitution, The Renewed Establishment of the Land, in 1627 legalized the hereditary power of the Habsburgs in the Czech lands and declared Catholicism the only permitted religion.

Non-Catholic were ordered either to leave the country or convert to Catholicism within six months. The result was a great wave of emigration, in which the Comenius family also went into exile.

For Comenius, Lešno in Wielkopolska became a new refuge, where he spent a total of 19 years of his life in three stays. Comenius found a second home in Leszno; he gained European fame thanks to works written in Latin, especially modern textbooks and pansophical works.

At the age of 50, Comenius was at the peak of his creative powers and there was considerable interest in his work in Europe. He even received an invitation to Paris from Cardinal Richelieu himself. Comenius’s main task was to write textbooks, but his real interest was increasingly focused on the main all-correcting work, the General Council on the Redress of Human Affairs.

The disaster for Jan Amos was the unfortunate news of the conclusion of the Peace of Westphalia in October 1648, which, despite Swedish promises, left the Czech lands under the control of the Habsburgs.

But even now, his vitality could not be broken by failures. His contacts with foreign countries (especially with England) continued, from whom he tried to get help for the Czech exiles. Despite the final confirmation of the Peace of Westphalia in January 1650, the Brethren Assembly decided not to dissolve the Unity of Brethren and to maintain it for the future.

In this new situation, Jan Amos Comenius welcomed the invitation of the Transylvanian Protestant princely family of Rákóczi to undertake the reform of their Latin school in Sárospatak. He thus had the opportunity to revive contacts with the exile congregation in Hungary and to try to gain new political support for the Czech exiles. He improved the local school and wrote many excellent, especially didactic, works (School through play, Orbis pictus). However, the intrigues of the rector of the school began to worsen Comenius’ position in Sárospatak, so in June 1654 he decided to return to Leszno.

At that time, again and for the last time, the hopes of the Czech exiles for the reversal of Central European conditions revived. A coalition of Sweden, Cromwell’s England and Transylvania was looming on the horizon. When the Swedish-Polish war broke out in 1655, the Swedish warrior king Charles X. Gustav first celebrated great triumphs. However, soon the military tide began to turn, Polish Catholic troops attacked and burned Leszno (considered a nest of foreigners and Protestant traitors).

Jan Amos and his family managed to escape at the last minute, but in the fire, he lost all his property, including the library and many valuable unfinished manuscripts.

In a temporary refuge in Frankfurt an der Oder, Comenius was given an invitation to Amsterdam in June 1656; he moved to the Netherlands, permanently this time.

His fourteen-year stay in Amsterdam was a time of a final creative uplift for him (it was here that he completed and published his many literary and scientific works). However, his ideas and efforts were already moving away from the reality of then Europe, dominated by power and economic interests.

He died in Amsterdam on November 15, 1670, amid work on an unfinished work at the age of 78, and was buried a week later, on November 22, in the town of Naarden, 20 km southeast of Amsterdam.

The final stop on Comenius’ long journey was the tomb in the church of the Walloon Reformed Church, with which the deceased had a very close personal relationship.

-

NEWSLETTER

Subscribe for our daily news