The exhibition delivers an overview of the remarkable career of Alberto Giacometti, a peculiar artist who has marked the world of modern art.

By Sarah Duchêne – Anglo American University

From Paris to Prague for the very first time ever, an impressive exhibition of Alberto Giacometti is taking place at the National Gallery Prague until the 1st of December. In collaboration with the Foundation Giacometti, more than 170 works trace the history of the artist including not only his sculptures but also paintings and drawings.

Through this chronological exhibition, viewers will discover his earliest works, and then follow his progress in Paris after his encounter with the Surrealists there. The outstanding number of works also reveals the artist’s polymath and perseverance.

Since his early childhood, Giacometti (born 1901 in Switzerland) was raised in art by his father, Giovanni Giacometti, who was an Impressionist painter. While most children play with toys at this age, Alberto made his first sculpture at the age of 13. He also made many Neo-Impressionist paintings in his youth. In 1922, he moved to the City of Lights to study at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière where his sculptures revealed his new interest in Cubism.

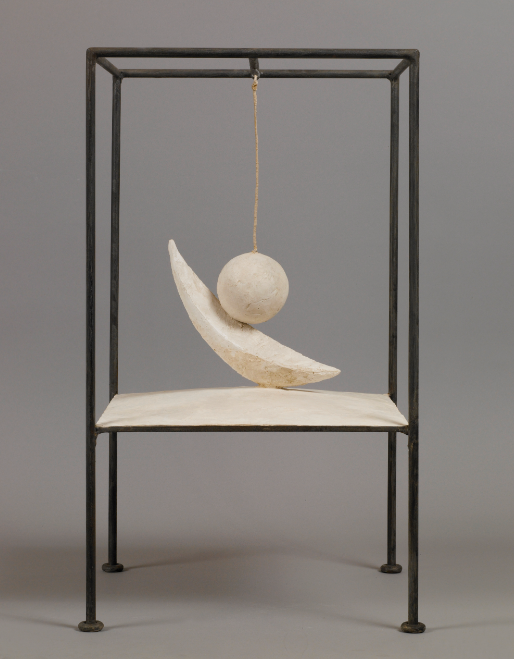

His entry into André Breton’s Surrealist circle was the turning point in his career. After this, Giacometti gained attention for one of his most famous sculptures from this time, Suspended Ball (1930-31). This floating ball on a crescent locked in a cage was described by Salvador Dali as the prototype for “an object with a symbolic function.” This unusual sculpture mixes dream and eroticism, and it is one of the centerpieces of the current exhibit in Prague.

Giacometti’s Surrealist phase ended a few years later. He became more concerned with the question of the human head and the model’s gaze, and less interested in movement. For him, the mystery of the human head became the seat of a human being from his perspective.

For models, he mostly used his younger brother Diego, or close friends only. His fascination with the head also appeared in many drawings and paintings. At this point, his shift from Surrealism seemed to be philosophical, as an Existentialist more focused on the human being. Jean-Paul Sartre even wrote essays about Giacometti’s art and his question of perception.

Besides the head, the size of the sculptures remains a special trait of Giacometti’s art. His early works were sometimes so tiny that they fell apart. One of his most famous tiny sculptures is the figure of Isabelle Delmer, one of his close friends, placed on a pedestal. The fact that they are so tiny reflected the distance he instituted between him and his models.

Giacometti once said, “But wanting to create from memory what I had seen, to my terror the sculptures became smaller and smaller.” His sculptures changed after World War II when he started to create the taller and highly slender figures that he is most famous for today.

Alberto Giacometti was not a typical artist; he lived only for his art. He had an unusual determination, a passion for his sculptures to the point that he almost lived in his studio. It looked like a mess; it was tiny and dark, but he liked it that way. To carefully look over his many sculptures, paintings and drawings is the only way to understand, or maybe not, the career of one the most influential artists of his century.

For more information about the exhibition, see the website for the National Gallery Prague.

Alberto Giacometti, Zavěšená koule, 1930–1931, © Estate Giacometti (Fondation Giacometti + ADAGP) Paris, 2019

Alberto Giacometti, Hlava muže na podstavci, 1949–1951, © Estate Giacometti (Fondation Giacometti + ADAGP) Paris, 2019

Alberto Giacometti, Stojící žena, kolem 1961, © Estate Giacometti (Fondation Giacometti + ADAGP) Paris, 2019