A new special tram has begun service in Prague to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the Prague Uprising and the end of World War II.

Decorated in the Czech national colors and titled “Prague, the City of Heroes,” the tram was officially unveiled on Tuesday, May 6, in Stromovka Park.

This Škoda 15T tram will operate across the city for the next six months, bringing history to life with visuals that honor the resilience and bravery of Prague’s citizens during the May 1945 uprising against Nazi occupation. The tram bears key dates and symbols of that period, offering a moving tribute to those who resisted.

According to Deputy Mayor Jiří Pospíšil, the initiative serves as a living reminder of how Prague’s history is intertwined with its everyday life. “The Prague Uprising is an extremely important moment in our history. This tram will remind both residents and visitors how essential it is to preserve and pass down these values to future generations,” he said during the launch.

Inside the tram, passengers will find informative panels describing not only the Prague Uprising, but also other crucial events from the final days of World War II in Czech territory.

Eleven themed displays highlight episodes such as the fire at the Old Town Hall, the return of Czechoslovak air squadrons, and the roles played by the Russian Liberation Army (ROA), Soviet forces, and American troops.

In addition to the tram, the city has launched a panel exhibition titled “V as Victory” at Mariánské náměstí in Prague 1. Open to the public until May 30, 2025, the outdoor display explores the liberation of Prague and the war’s closing chapter. Full details are available here

Another exhibition, “Old Town Square in Flames,” is now open at the Museum of Memory of the 20th Century.

Would you like us to write about your business? Find out more

On Thursday, May 8, Prague will bring its wartime past to life with a large-scale reenactment of the 1945 Prague Uprising.

The event, titled “Barricade”, will take place in the Nusle district, where some of the bloodiest clashes between Prague’s resistance fighters and the occupying Nazi forces took place during the final days of World War II.

Admission is free, and the action will take place directly on the original streets of the uprising: Táborská, Petra Rezka, náměstí Generála Kutlvašra, and Na Květnici.

Around 400 historical reenactors, dressed in period uniforms and armed with authentic weapons, will recreate the scenes of urban warfare that marked the city’s liberation.

The reenactment will feature live battle scenes, projected on large outdoor screens and narrated in real time to provide historical context for the audience.

What sets this event apart is its authenticity: visitors will see original WWII military vehicles and equipment in action, offering a rare connection to the past.

Beyond the battle scenes, the event will include several side programs, such as a retro fashion show, immersing visitors in the cultural atmosphere of 1945 Prague.

The event is part of Czechia’s annual Victory Day commemorations, held on May 8, marking the end of World War II in Europe.

Would you like us to write about your business? Find out more

Eighty years ago, in the final days of World War II in Europe, Czech citizens and members of its resistance launched a final assault against the Nazis.

The Prague Uprising lasted for five days and came to represent a symbol of Czech resistance in World War II.

Czech police officers burst into the radio station at Vinohradská Street and battled with the SS soldiers who were already occupying the building.

At 12:33, Prague radio called on all Czechs to take up arms in the organized resistance: it was the beginning of five days of fierce fighting that would see thousands lose their lives.

With the sound of combat as a backdrop, the announcer asked for public support with the following message: “Calling all Czechs. Come to our help at once. Come and defend Czech Radio. The SS are murdering Czech people here. Come and help us. You can still get through the Balbínova Street entrance…”

Resistance fighters in other parts of the city took over the Gestapo and SiPo headquarters. Civilians finally removed the hated German signs and began to attack and disarm the Germans. Barricades were built in the streets.

Antonin Sum, a teenager at the time, was involved in the resistance. “The uprising started in Prague,” he said. “You could see in the streets, as I saw myself, people with guns, which was absolutely impossible before. They were guns that had been hidden away somewhere underground in caves.… It was just the start, but nobody knew what was practically going on.”

In scenes reminiscent of European uprisings in the 19th century, cobblestones were torn from the streets to form the foundations of barricades. Carts, vehicles, and trolleys were overturned to block key intersections, and snipers took to the rooftops overlooking choke points.

By May 6, thousands of citizens had constructed over 1,600 barricades overnight. German reinforcements made their way to Prague and the fighting continued to escalate.

The Luftwaffe began to bomb areas of the city, hitting the radio broadcasting building, barricades, and civilian apartments. A battalion of the Russian Liberation Army (ROA), a German army unit made up of Soviet POWs, defected and came to the aid of Czech defenders, successfully disarming thousands of German troops.

On May 7, while German leaders were signing their unconditional surrender to the Allied forces in France, German forces in Prague launched a massive attack on the city.

Upon hearing the news of Germany’s surrender, the ROA, who had been successful in slowing the German advance on the city, left Prague to surrender to the US Army. With a majority of the ROA gone, the ill-equipped resistance fighters suffered against the reinforced German units and lost much of the territory they gained over the first days of the uprising.

Fighting continued in Prague even after the official Nazi surrender on May 7th. On May 8th, the Germans launched an air raid followed by a ground attack, with SS forces retaking key positions like the Masaryk rail station, where they brutally executed approximately 50 captured resistance fighters.

Facing critical situations on both sides and with Allied assistance still absent, Czech and German leaders negotiated a ceasefire. The agreement allowed German forces to pass through Prague westward on the condition of disarmament.

On the morning of May 9th, German forces left Prague. Later that day, the Soviet Red Army arrived and subdued any remaining German units in the city. Czech citizens jubilantly flooded the streets to welcome the Red Army and celebrate their liberation.

Eighty years after the Prague Uprising, the city will mark the anniversary with a powerful mix of remembrance and celebration.

Prague 1 is organizing two days of events that will take over some of the city’s most iconic spots on May 5 and May 8.

“We’re not just marking a date—we’re remembering the bravery that stood firm when everything seemed lost,” said Terezie Radoměřská, mayor of Prague 1. “These moments shaped our identity. And they remind us that freedom isn’t something to take for granted—it was paid for with lives.”

May 5: Commemorating the Start of the Uprising

The commemorations begin at 10 a.m. on May 5 at the Old Town Hall, where officials and members of the Czechoslovak Legionary Community will gather by the memorial plaque to honor those who died during the 1945 uprising. A short ceremony will also be held in the nearby Cross Chapel and courtyard.

Later that afternoon, the Old Town Square will turn into a kind of living history experience. At 2 p.m., an event titled “Old Town Square in Flames” will bring the past to life through sound, visuals, and performance. Organized by Prague City Hall, Prague 1, Media Park, and the Museum of Memory of the 20th Century, the program includes:

- The bells of the Church of Our Lady before Týn ringing across the square

- A public reading of names of those who fell in the uprising

- An open-air exhibition with virtual reality elements

- Evening film screenings related to the final days of the war

At 7 p.m., the action shifts toward the riverfront. A symbolic barricade will be constructed between the National Theatre and Café Slavia, recreating the resistance effort that played out in this very area eight decades ago.

The project, called “To the Barricade! The National Theatre, Occupied and Resisting,” will feature a memorial procession, a live broadcast by Czech Television, a performance by the Kühn Children’s Choir, and a set of historical exhibits paying tribute to artists and performers who joined the armed resistance.

May 8: National Remembrance at Wenceslas Square

On May 8, the anniversary of the end of World War II in Europe, Prague will once again become a stage for public remembrance.

The nationwide project “Let’s Not Forget 80”, organized by the non-profit Paměť národa (Memory of Nations), will unfold in the lower part of Wenceslas Square, with Prague 1 supporting the effort with a 100,000 CZK contribution.

From noon until the evening, the square will host a series of interactive events, including:

- Personal stories and memorial exhibitions

- Public talks and appearances by well-known Czech personalities

- Live concerts and performances across the square

At 7 p.m., the country will pause for a minute of silence—a symbolic gesture meant to unite people across Czechia in shared remembrance.

Would you like us to write about your business? Find out more

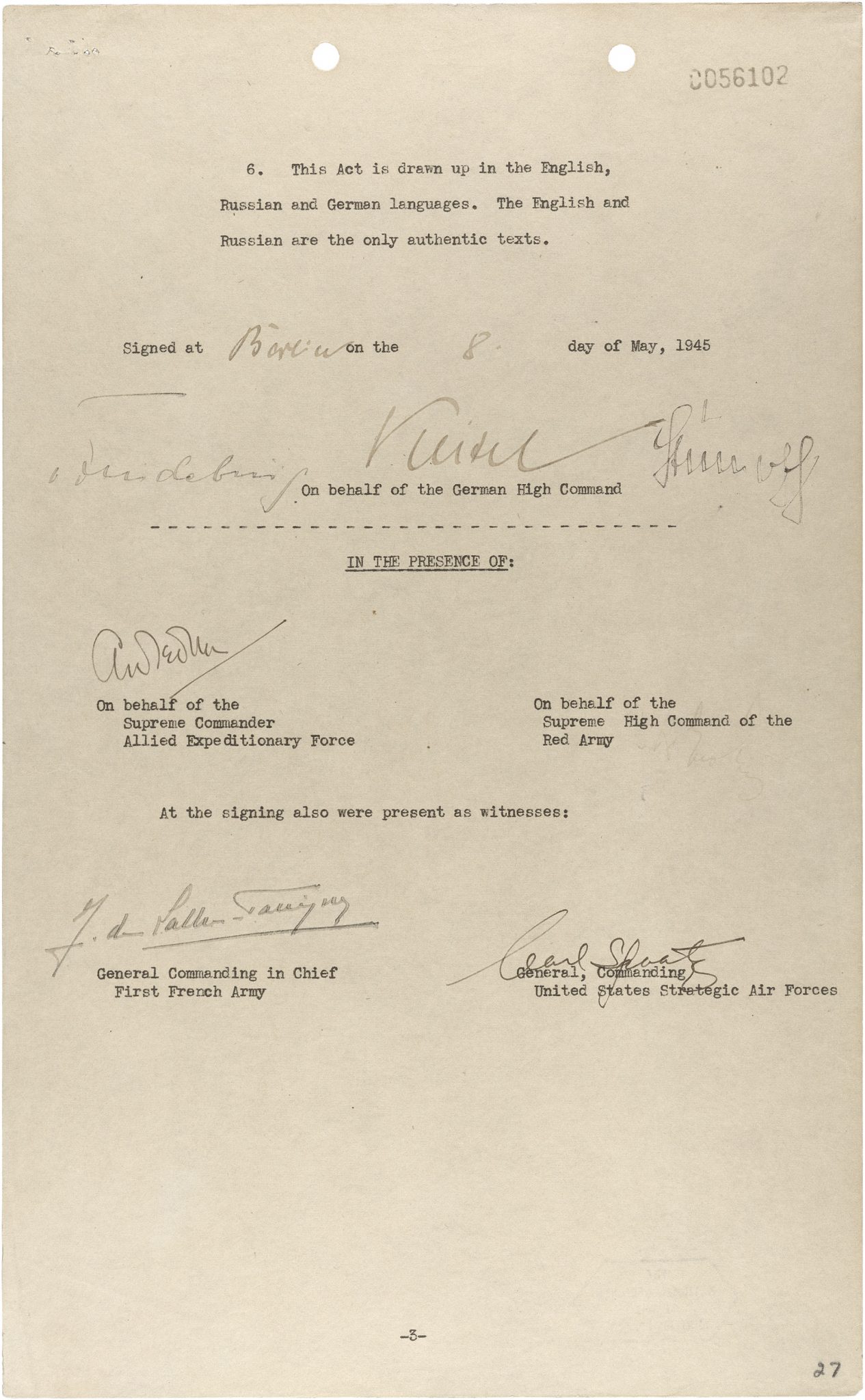

May 8 is, as in several European countries, a national holiday in the Czech Republic for the observance of the anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe; it was on this day in 1945 when Germany’s formal surrender was signed in Berlin.

On May 8, with Allied troops approaching from west and east, the Czechs negotiated a cease-fire with the Germans.

That afternoon, an agreement was signed in Prague between the com-mander of the Czech National Army and the German commander. All fighting would cease at 8 p.m. that evening.

All German army units, SS troops and German State organizations would begin to leave Prague and its surroundings. The Czechs had liberated their capital.

Entering Prague in the wake of its self-liberation, the First Ukrainian Army, commanded by Marshal Konev, acquired the prize that Stalin had so desired.

A previous agreement between American and Russian forces stated that the Red Army would be the one to liberate Prague; however, some American Army forces had come as far as the suburbs of Prague, and some negotiators persuaded General Toussaint, commander in charge of the German forces, to agree to the cease-fire.

The American tanks that had entered Pilsen in advance of the infantry, bringing Czechoslovakia into the European Theatre of Operations of the United States forces, were soon ordered back, as part of Eisenhower’s agreement with the Soviet High Comand that western Czechoslovakia would be in the Russian sphere. ‘

The date was officially named Liberation Day, although it was the Czech people, with KONR (Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia) backing, who liberated the city the day before.

Between 1,700 and 2,000 Czechs were killed in the uprising, and thousands more were wounded.

In the course of the Prague Offensive, the losses of the Red Army amounted to 50 thousand people, while over 140 thousand were lost in the battles for Czechoslovakia. Many units and regiments were awarded honors and medals for their performance in the operation.

The exile government returned to Prague on May 10 and promptly dissolved the National Council. Resistance leaders were delegated to minor positions and were not represented in the new national government.

Soviet forces now occupied almost all of the country, and within months, under the Potsdam Agreement, hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans were expelled from the Sudetenland.

Under Soviet occupation, the fledgling democratic government went the way of Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, and other countries in the Russian sphere of influence. In 1947, the Slovak Democratic Party was made virtually impotent. By February 1949, all Czech democratic parties were eliminated, and a few months later the Communists officially took over control of the government.

Prague liberated by Red Army in May 1945 – Marshall Konev

Source: www.russianphotographs.net

On May 7th, freshly arrived Wehrmacht and Waffen SS units started attacking from the North and east of Prague.

Some of the most intense fighting took place in Strašnice, just east of Žižkov.

The district was important because it housed the reserve radio station, to which the Czechoslovak broadcasters were forced to move after a 500kg bomb dropped by a German jet-fighter had destroyed their equipment in the main building of Czechoslovak Radio.

Luckily a resistance unit had managed to capture some Hetzer tank destroyers and keep the Germans away from the radio station.

German bombers flew in on May 7 and bombed the city, causing the destruction of most of the Old Town Hall; the centuries-old building was almost completely gutted and had to be torn down.

The top of the tower was also destroyed, and damage was caused to the famous Astronomical Clock. The Germans’ superior firepower gradually overwhelmed the Czech fighters, whose ammunition was insufficient.

While all this was going on, German leaders accepted the inevitability of unconditional surrender.

Armored and artillery units pushed their way through the barricades, using civilians as human shields along the way. Upon hearing the news of Germany’s surrender, the Russian Liberation Army (ROA), who had been successful in slowing the German advance on the city, left Prague to surrender to the US Army.

On May 7, 1945, the German High Command, in the person of General Alfred Jodl, signs the unconditional surrender of all German forces, East and West, at Reims, in northeastern France.

At first, General Jodl hoped to limit the terms of the German surrender to only those forces still fighting the Western Allies. But General Dwight Eisenhower demanded a complete surrender of all German forces, those fighting in the East as well as in the West.

Franklin D. Roosevelt LibraryNazi Col. Gen. Alfred Jodl, center, signs the instrument of surrender ending Nazi Germany’s involvement in World War II in Rheims on May 7, 1945.

In Prague, May 6 was a day of crisis. The Germans retook the main radio station, but Czech partisans continued broadcasting from another base.

About half the city was occupied by the resistance, and his scattered units needed time to concentrate.

Barricades and snipers made treks to assembly points hazardous affairs, but the Germans were able to gather units close to the radio station.

Reinforced with the SS units, the Germans struck at the radio station. As resistance fighters tried to stem the tide of infantry, assault guns, and tanks, a new voice came over the airwaves begging for help from the Allies.

“Prague is in great danger! The Germans are attacking with tanks and planes. We are calling urgently our allies to help. Send tanks and aircraft immediately. Help us defend Prague. At present, we are broadcasting from the radio station. Outside, there is a battle raging.”

The voice belonged to William Grieg, a Scottish POW who had escaped from the Germans. Grieg found himself in the middle of the uprising and was asked by the Czechs to make the appeal. With fighting erupting all around him, Grieg calmly sat in front of the microphone and sent out the urgent request.

Meanwhile, the Head of the Russian Liberation Army Andrey Vlasov received a request from the commander of the first ROA division, General Sergei Bunyachenko, for permission to turn his weapons against the Nazi SS forces and aid Czech resistance fighters in the Prague uprising.

Vlasov at first disapproved, then reluctantly allowed Bunyachenko to proceed. Some historians maintain it was the bitterness of the ROA against the Germans which caused them to switch sides once again, while other historians believe the sole purpose of this action was to win favor from the western Allies and possibly even the Soviet side, in the light of the nearly completed military annihilation of the German Reich.

The Czechs fought bravely, but the Germans were too strong. They recaptured the radio station, but Czech engineers had already removed enough equipment to set up another broadcasting center in a safer part of the city.

Grieg was called back into action later during the uprising to ask for an Allied airstrike against a German armored column that was advancing on the city. Unlike his first appeal, that request was answered and the German column was decimated.

Photo: Pavel Žáček

Photo: Pavel Žáček

Photo: Pavel Žáček

Photo: Pavel Žáček